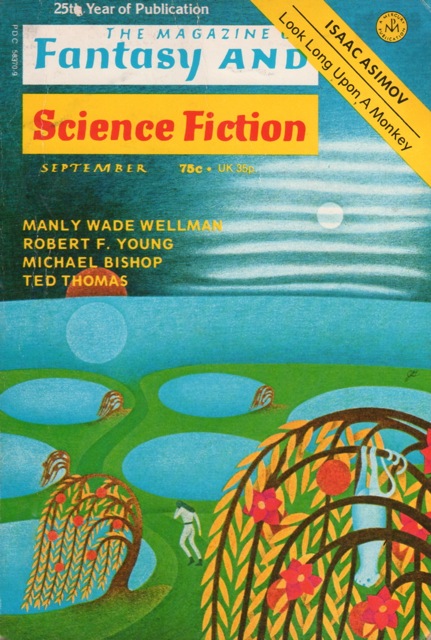

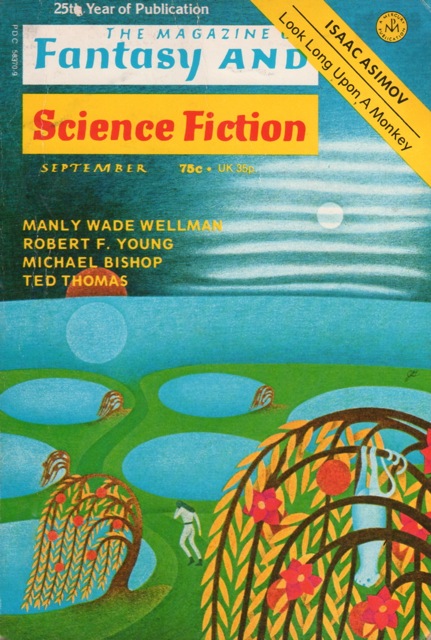

In September of 1974, age 14, I bought my first issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction from a newsstand. This was one of the first times I encountered short fiction live, as it was happening, rather than from one of the relatively stale collections stocked in the library or supplied by the Science Fiction Book Club. I discovered in that issue the latest stories by several young writers I had never heard of: Tom Reamy, Michael Bishop, and Charles L. Grant. The cover was inspired by Bishop’s dreamlike planetary adventure, “Cathadonian Odyssey”; Tom Reamy’s “Twilla” featured a striking glimpse of a genie’s enormous schlong; but it was Charlie Grant’s “The Rest Is Silence” that struck me most deeply. (Well, I confess I do still think of that genie dick from time to time.) I did a lot of my reading, back then, in the back seat of cars, with the freeways of Southern California gliding past; and I still remember how the bright hot afternoon was pierced by a moment of dark chill and stillness as I reached the end of the Grant’s story.

From that moment forward, I sought and devoured every one of his tales, wherever I could find them. A couple dozen Grant stories appeared over the next few years, in various magazines and anthologies, and I read most of them. They were all beautifully written, lyrical, more occupied with atmosphere and character than with the shocking effects of many other writers at the time, who were trying to one-up The Exorcist in the gross-out department. His distinctive titles suggested poetry as much as genre horror: “When All the Children Call My Name,” “A Glow of Candles, A Unicorn’s Eye,” “The Dark of Legends, The Light of Lies”…

As he shifted his energy into writing novels, his output of short fiction dropped off dramatically. But Grant’s influence was already in effect on my own writing. Among my ambitions as a writer of horror and dark fantasy, I now valued the quiet chill of Charlie’s work, and always looked for opportunities to emulate it.

Grant was often compared to Ray Bradbury, perhaps because he wrote a number of stories that focused on childhood in ways reminiscent of Bradbury’s own nightmarish stories of youth; and no doubt Bradbury was a huge influence. But his work reminded me more of Rod Serling. Not the Serling of the science fiction twist, but the author of “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar,” who drew deeply from the hearts of haunted people. Serling and Grant were both veterans, both marked by their wartime experiences, and I wonder if this is one of the reasons I found something similar in their work. As far as I know, Charlie never wrote openly of his time in Viet Nam or used it as a setting for fiction (I would love to hear otherwise), but there is no question the stories sublimate his experience and come from a darker place perhaps than Bradbury’s Midwestern carnival idylls. Both wrote of death, but while Bradbury’s prose seems ultimately innocent and scarcely scathed, Charlie appeared to know much more of the wounded, of how one lived with scars and struggled on through injury.

In the summer of 1977, after a week at a small wooded lake in Oregon, I came home and wrote an aimless, atmospheric story about weird things in the woods. Its wordy title, “A Peaceful Summer by the Lake of Shadows,” marked it as something written under the spell of Charles L. Grant. That October, I carried the manuscript with me to the Third World Fantasy Convention in Los Angeles, and late one night, in a smoky hotel suite, I introduced myself to Mr. Grant and asked him if he might read it and give me feedback. I believe I must have written him some fan letters by this time; but even so, he had no particular reason to accept the manuscript. Still, he took it with him, and a few days later sent it back to me with some notes. I no longer have his reply, but I know it was a gracious one, even as he gently let me know that I had a long way to go.

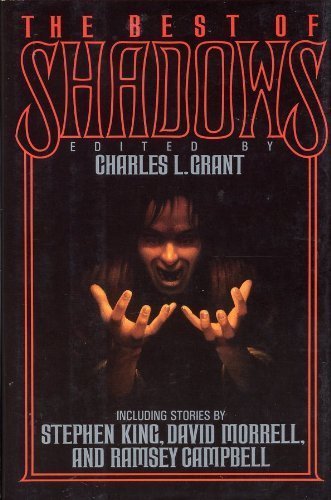

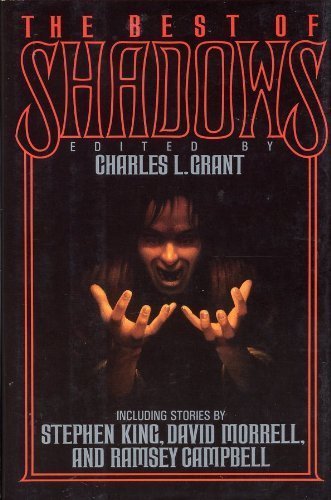

Around this time, he announced the creation of the Shadows series. The ultimate validation for me at that time would be to know I’d written something worthy of inclusion in the volume. I almost certainly pestered him with multiple submissions, although it couldn’t have been many, since I was just heading off to college and my own writing tapered off to almost nothing for a few years. It wasn’t until he was reading for Shadows 6, with the series well-established, that I sent him a very minor short story called “Sneakers.” Charlie seemed relieved that he could finally justify publishing something of mine, and despite the very un-Grantish one-word title, you can see his influence in the way very little is seen directly, and most is told literally through whispers. I always hoped to sell him something more substantial, but I was moving away from horror at that time, in search of my own voice. (And apparently Charlie liked the story a bit more than I realized, because while looking through old boxes of books, I discovered that he’d troubled to include “Sneakers” in his Best of Shadows anthology…a fact I had forgotten until yesterday.)

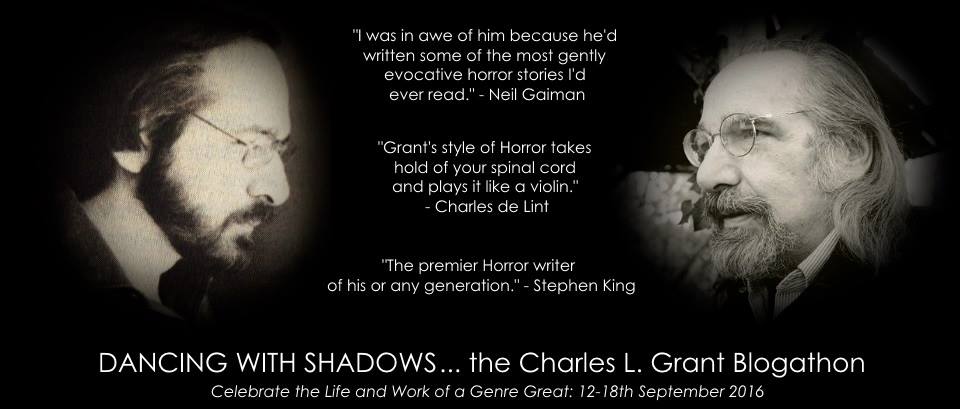

Years later, I wrote a story that in retrospect seems a much better example of the Charlie Grant influence: “Cell Call.” Charlie was certainly much on my mind around the time I wrote “Cell Call.” He was gravely ill, and his health was a topic of much concern among the community of writers and fans who admired him. I had never gotten to know him beyond our early correspondence, but I was glad to join others in writing to let him know how much his work had meant to me. I hope he received many such letters.

Despite my love of his work, I read only a few of Charlie’s novels. Around the end of the Seventies, he moved away from short fiction, commencing a prolific period of writing novels under several different names in addition to his own. This was the time when I was drifting away from genre in general, so I read fewer horror novels, including Charlie’s. But though I return again and again to read horror from every era, it is still those stories of the mid-to-late Seventies that strike me as the purest, finest examples of his work. While most of Charlie’s novels languish out of print, I note that editors continue reappraising and collecting his short stories in such volumes as Scream Quietly: The Best of Charles L. Grant (2011), edited by Stephen Jones.

Even so, “The Rest Is Silence” is still fairly hard to find. It was nominated for a Nebula Award the year it came out, but it is not in the last few collections of his best work. This strikes me as an oversight. It’s time to go digging into my boxes of old magazines. It’s time to appreciate Charles L. Grant anew, before the silence settles in completely.

Won’t you join me?