Sea of Tranquillity

It was the year 1969. In the van, Jeff was broasting alive, and his tongue had turned to pumice, but he hardly felt the July heat. The freeway shimmered as if it were aflame, and where the illusion was strongest the boy imagined he could see through cement to the surface of Earth’s moon. Somewhere high above Burbank’s smoggy gray sky, the lunar excursion module crouched like a spider on stilts. Down here, lanes merged and diverged, cars sped from near to far away in seconds, and two ladies in black changed a tire on a black T-Bird by the side of the road. Up there, astronauts waited to walk.

When they parked at a supermarket, Jeff begged his dad to leave the key in the ignition. He leaped to turn up the radio, but the engine cover seared his legs. “Yow!”

“Careful, Jeff,” said his mother, wearing dark glasses without depth or surface. “I’ll get it.”

His brother Eddie said, “Hey, Mom, lookit—”

“Sh!” Jeff said.

He listened to the static, hoping to catch the voices of astronauts or Houston Control.

“Drink Royal Crown Cola—”

“Don’t shush me,” said Eddie, flicking Jeff’s earlobe.

Jeff spun around, ready to punch his brother.

“Boys, I’ll turn it off.”

“He started it!” Jeff said.

“I’m in no mood for this.” She snapped it off. “Here’s your father.”

“See?” said Jeff, glaring.

“I see a monkey,” said Eddie.

Their dad got in, and they drove on into Burbank.

#

Jeff’s aunt and uncle lived in a tiny Spanish-style house with white stucco walls, a roof of overlapping pink tiles, and a yard guarded by a picket fence. As they parked. Uncle Lou came out on the porch with a can of Coors. He was a tall redhead, as broad as the doorway and crimson from sunburn.

Jeff was the first one out of the van. “Uncle Lou, have you seen it? They’re on the moon!”

As he ran through the gate, he heard barking. Too late, he remembered Mab.

The black Labrador retriever bounded around the side of the house. He yelled as she knocked him down, then stood over him drooling, her paws on his shoulders.

Lou laughed as he pulled the dog away. “You’ll never be an astronaut if you can’t get past Mab.”

“There’s no dogs in space,” Jeff said, getting to his knees. “A dog went up with Sputnik, but she burned up on reentry.”

Mab strained at her collar, trying to pounce on Jeff’s dad as he came through the gate. “How’s the space shot?”

Lou took his hand. “Bad reception, Billyboy. Come on in.”

Jeff was the first inside. The TV gave the living room a blue glow. On the screen was a model of the LEM in its gold foil wrapper.

“Oh, boy!” Jeff said. “Color.’’

“Hello, boys,” said Aunt Maddy.

Her dark hair was up in a bun, and her lipstick shone a weird shade of purple as it caught light from the TV. Jeff tasted cherry wax when she kissed him. “Gosh, it’s good to see you two.”

“It’s only been a week,” he said.

“Do you want something to drink? Juice or soda pop?”

“RC,” Eddie said.

They followed her into the kitchen, where she filled glasses with ice and cola.

“Do they have soda pop on the moon?” Eddie asked.

“Not yet,” said Jeff. “They eat Kool-Pops and stuff like toothpaste. Hey, Aunt Maddy, I got some Sputnik bubble gum.”

“You know all about space, don’t you?” she said. “I bet you’ll be the smartest astronaut they ever see.”

“He’s no astronaut,” Eddie said.

“I will be. I’ll be the first man on Mars.”

“I’ll bet.”

“Okay, boys,” said their mother, entering the kitchen. “You know you shouldn’t be drinking that stuff.”

Jeff slipped past her into the living room and dropped onto the sofa. RC stung and hissed in his mouth. His dad had set up a camera tripod in front of the TV and was taking his Nikon from the case while Walter Cronkite described the leg of the lunar excursion module.

The screen showed static.

“Hope this clears up,” said his dad.

Cronkite said that they were looking at the lunar surface now. Crestfallen, Jeff peered at the fuzzy image. There was no stunning landscape of sharp horizons and vast craters, no Earth floating moonlike in star-prickled space.

“It has to get better,” he said.

“You wish,” said Uncle Lou, crossing to the front door and going out.

“Jeff,” said his dad, “could I get you to hold the camera?”

As he stood, his innards lurched from carbonation.

The screen door squealed, and Mab bounded inside. She leapt onto Jeff, bathing him in slobber while he called for help.

“Hey, watch the camera!”

Lou came back in, pulled Mab away, and thrust her outside.

Eddie, giggling, said, “I don’t want to watch the stupid old moon. Isn’t there a game on?”

“Why don’t you look?” said Uncle Lou.

“Lou,” said Maddy, “this is the moon.”

The screen was a flurry of black and white; color TV made no difference. Walter Cronkite’s voice gave way to the faraway hiss of the astronauts. Neil Armstrong said—

“If you want a better car, go see Cal!”

Eddie had changed the channel by remote control.

“Hey!” Jeff shouted.

“Leave it on the moon,” said their dad. “This is history.”

“Yeah,” said Jeff.

“Well, they’re not doing anything yet,” said Jeff’s mother. “It won’t hurt for a minute.”

Eddie wandered from the TV, oblivious to the condition he had created.

“Go see Cal, go see Cal, go see Cal!”

Jeff’s dad reached for the knob.

Lou said, “Wait a minute, Bill. Let’s see what this is.”

“It’s a commercial.” Disbelief was plain in his voice. He shook his head and turned back to the moon.

Jeff saw Maddy lay a hand on Lou’s arm and look into his face.

“Get me another beer,” he said.

“Get it yourself,” she said.

“I’m close,” Jeff’s mother said, and ducked into the kitchen.

The picture wavered like a tapestry of lunar snow and glare, but Jeff was determined to figure it out. He thought he could see ghosts moving in the snow. Then the image settled, and he saw reruns of the Apollo 11 liftoff: a black-and-white torch blasting ramparts aside, flaring high, and dwindling into blue sky. Animated illustrations showed the rocket’s stages parting in flight; the relative distance of the moon; the ship’s orbital path and the loop of its planned return, a dashed infinity sign.

“What sort of pictures do you think you’ll get, Bill?” Lou said.

“I don’t really know.”

“Can’t imagine they’ll come out.”

“Uncle Lou,” Eddie said, “can we see your Vee-nam pictures? You always say you’ll show us your chopper.”

“Not now.”

“Why not?” said Maddy. “I’ll get them.”

He caught her arm, repeating, “Not now. Not with all this.” He gestured with his fresh beer. “It’s bad enough as it is.”

She drew away from him and went into the kitchen. Jeff watched her open the fridge and stare inside, her face pale. Reaching for a beer, she glanced over, saw him watching her, and smiled.

“Tuna sandwich, Jeff?” she called.

“Please.”

She brought in a foil triangle and sat next to him on the sofa while he unwrapped it.

“When I go to Mars I’ll get you to make my lunches,” he said, chewing.

“It’s a deal.”

“And when I get there I’ll send a message to you.”

“Really? What will you say?”

“I don’t know. ‘We did it.’”

She laughed. He offered her half of his sandwich.

“Your Uncle Lou doesn’t think we should waste energy sending people into space.”

“Christ,” said Lou.

“He says we should take care of our problems on Earth before we take off for the moon.”

“I guess,” said Jeff, saddened. He looked at his uncle, who was watching TV with a surly smile.

“I don’t think he believes in stars anymore.”

“That’s like not believing in Walter Cronkite,” Jeff said.

The camera clicked.

Maddy laughed. “Oh, Bill, you’re a riot. Taking pictures of pictures.”

“They’ll be valuable someday. Jeff and Eddie will be able to look at them and remember this.”

“If they remember to look,” said Lou. He got up and walked into the back of the house.

“What’s with him?” asked Jeff’s dad, her brother.

“I don’t know, Bill.”

“How’ve you been, Maddy?” asked his mother, sitting beside Jeff. With adults on either side, he felt overwhelmed. He slipped from the sofa and stood by his father, still focusing on the television.

“Hey,” said his dad. “I think this is it. Turn up the sound, Jeff.”

He hurried to the TV. An astronaut spoke:

“It’s kind of soft. You can kick it around with your foot.”

Suddenly the picture changed into a screaming blur. Jeff leapt back, swept by chills. What had they found up there?

“My God!” Maddy said, running for the hall. “The hair dryer!”

“I’m not touching it!” Lou yelled from the bedroom.

The picture calmed. Something moved into the lunar view. Jeff twisted the focus knob and played with the tint. The moon turned red, then yellow, and the haze got worse. The sound began buzzing and throbbing.

“Let me,” said Jeff’s dad. He worked the knobs, and the picture returned . . but they were too late.

“—for mankind.”

Jeff yelled, “We did it!”

“Damn,” said his dad. “Get out of the way, Jeff.” He stepped back and accidentally hit the tripod. His dad swore and swatted at him, then took picture after picture. Amazingly, the clarity remained. Neil Armstrong was on the moon. Jeff could almost see what it looked like.

Maddy came out of the hall, weeping. Behind her, the bedroom door slammed shut.

“Maddy,” said Jeff’s mother, hurrying over to her.

Jeff looked back at the TV, imagining the moon hanging far out in space, a tiny man standing practically barefoot on its surface. It was sharp and impossibly clear, but it was all black and white.

“Hey,” said Jeff’s dad, crossing to Maddy. “What’s wrong?”

She shook her head, hiding her face. “Reruns. That’s all he’s been saying all morning. They already walked. I don’t know what’s going on with him.”

Jeff got goose bumps. Reruns?

The adults went into the guest bedroom, leaving him alone.

Reruns, like The Honeymooners?

He forgot the TV until, by itself, the picture changed from the moon to a bottle of Ivory Liquid, then to acres of cars, a bullfight. He twisted the knob but with no effect. A dozen pictures flew past. There went the moon!

Eddie laughed. Spinning, Jeff saw him punching buttons on the remote-control box.

“Stop it!”

Jeff flung himself at Eddie, and they both landed on the floor, pummeling each other. Excited by their cries, Mab worked open the screen door and rushed in. Jeff curled into a ball and kicked out, knocking Eddie across the room but letting the dog closer. She leapt all over him while Eddie made his escape. Jeff struggled up and ran out, Mab behind.

He chased Eddie once around the house, then the heat overwhelmed all of them. They stood panting and sweating in the front yard.

“You kick like a girl,” Eddie said.

“Shut up.”

Jeff opened the door and went inside. As his eyes adjusted to the shadows he saw a huge silhouette rising against the TV. It was Uncle Lou, his hands full of shiny brown ribbon. The camera lay on the floor, its back wide open.

“Unc—”

Lou dropped the exposed film, taking a step toward Jeff.

“I heard Mab in here,” Lou said.

“But she went out with us.”

Behind a smile, Uncle Lou looked murderous. His huge hands reached for Jeff.

The other adults came out of the guest room.

“Oh, no,” said Jeff’s dad. “What happened here?”

“Mab got into the camera,” Lou said. “The boys were roughhousing.” They all looked at Jeff. Eddie stayed outside.

“Crap,” said his dad, gathering the ruined film in his arms.

Jeff looked for the moon on TV, but all he saw was President Nixon on the telephone. The adults kept a funereal silence while Nixon congratulated the astronauts.

“No one cares about you,” Jeff said to the President. “We want the moon. Dad . . . Dad, is it true that it’s a rerun?”

“They walked late last night, yes.”

Eddie spoke through the screen door. “The TV Guide says there’s a scary movie on. I saw part of it once. It’s about this boy who finds out his parents are Martians.”

“The one with the sandpit?” Jeff asked.

“There are men on the moon and you want to watch monster movies?” said their dad.

Jeff shrugged, feeling guilty, but Eddie came in, and together they hunted for the remote-control box. Their dad sighed and said he would go get more film and beer. Jeff nodded at Eddie, who changed the channel. Aside from the moon, a few commercials were showing; there was no sign of the creepy movie. They waited for a Cal Worthington ad to end. Uncle Lou sat in his deep armchair. Jeff watched him from the corner of his eye. Uncle Lou had ruined the film, like he tried to ruin everything. Bad reception, Aunt Maddy in tears, reruns. It looked like a plot to ruin the moon shot.

“Mars is where I’m going when I grow up,” Jeff said defiantly.

Lou laughed. “First you want the moon, then Mars. When will you give up?”

“Never.”

Lou’s smile faded. “That’s tough,” he said, and grinned again, but this time it was like a pat on the head, as if Jeff were a baby.

“Oh, I’ll do all right,” said Jeff.

The commercial ended, and more moon appeared.

“I can’t find it,” Eddie said. “I’m going out to play with Mab.”

Jeff saw an astronaut . . . two? It was hard to tell. They were moving around an object that seemed an illusion of the bad reception, another ghost or double shadow. He made out black-and-white stars and stripes.

“There we go again,” Lou said under his breath. “Do it first. Jeff, you know why that other Apollo burned up on the launchpad?”

He shook his head, wary.

“We were in a big hurry,” Lou said. His eyes looked like Maddy’s, but the tears were held in place, and that made all the difference. “Such a hurry that we didn’t make room for a fire extinguisher. We pushed to get on the moon by 1970 for no good reason. Kennedy’s promise. That ship’s a piece of second-rate junk because we won’t take the time to build something good, something safe. It’s a game to get your mind off the real problem—the war.”

Jeff said nothing. Mab barked, and in the back room Aunt Maddy’s voice sounded high and choked. He watched the screen, the flag, the astronauts. A junk ship? He thought he was going to cry. Uncle Lou was trying to make him cry. Well, he wouldn’t.

He wished he could find that science-fiction movie with the sandpit and the buried spaceship. Fakey Hollywood fright, all eerie music and costumes, would be comforting by comparison to Uncle Lou.

#

“You drank too much RC,” said Jeff’s mother. “I’ll bring you a Tums.”

Jeff and Eddie lay in a strange bed in the guest room. Jeff was sure he would not be able to sleep because it was still early. He thought he heard Laugh-In in the living room.

When his mother returned with a pill, she asked, “Did you like the moon landing?”

Eddie said yes. Jeff said, “It was okay.”

“Go to sleep now. We’ll get you up in a few hours, we’re not staying all night.”

She closed them into the dark, and Jeff became instantly dizzy. The ceiling spun like a horseless carousel. He touched sleep and bounced back, as if from a black trampoline. The voices in the living room were soft until the TV went off and silence amplified them. Eddie turned over and jabbed Jeff’s ankle with a toenail. He stifled a complaint when he saw that his brother was asleep.

“Eddie?” he whispered.

No answer. Eddie’s breathing deepened, a sure sign of sleep, though he never slept so easily at home. Maybe there had been something in the burgers Uncle Lou had bought. But he was wide awake.

He had a theory.

Uncle Lou was not human.

He got out of bed, pulled on his pants, and went to the window, which was open to let cool air circulate. The screen was fixed by a rusty hook, and he had to be careful not to wake Eddie as he slipped the latch. He went over the sill into the backyard.

“Oh, no.”

Mab was waiting, but she made no sound. He patted her big head, then crept to the nearest corner of the house. Mab followed him with apparent interest.

“I wonder if you know,” he whispered, playing with her ears. “Is Uncle Lou a bad alien? Has he got a spaceship somewhere and some weird machine to mess up the TV? He wouldn’t put alien stuff in his bedroom. I think it must be in the garage.”

The screen door slammed and Jeff heard footsteps going to the sidewalk. Uncle Lou came into view and walked into the garage. A light came on inside . . . a faint, red light that showed through a tiny window.

“That must be his laboratory,” he said.

He climbed onto a section of picket fence that ran below the window and peered into the garage. The glass was covered by a sheet of brittle red plastic, but he could see Uncle Lou. There was a workbench covered with tools at the rear of the garage; an old car with its hood raised took up most of the space. Lou pulled a huge box down from a shaky shelf and dropped it on the floor. He took out a few sheets of newspaper and stared into the box.

The fence swayed under Jeff’s weight as he leaned closer, trying to see what was in the box. Uncle Lou reached in and took out a magazine. Its edges crumbled into dust, little flakes drifting over the car. The cover showed a rocket ship, a silver needle flashing through the blackness of interstellar space. Amazing Stories.

He searched his uncle’s face and saw tears in the bleak red light, the tears Lou had held back earlier. Embarrassed, he tried to jump down from the fence, but his cuff caught and he fell on the grass. Mab barked and he pushed her away. Rolling over, he looked for stars, but the night was hazy. The only lights in the sky were roving spotlights and the usual glow from downtown. The moon was nowhere to be seen.

“Jeff? Hey, Jeff, is that you?” It was Uncle Lou, coming closer. He hopped the fence and walked over to Jeff. Mab whined. He knelt in the grass.

“Jeff, I’m sorry if I hurt your feelings.”

“You didn’t,” Jeff said, finding himself angry but wishing he were not.

“I wanted to go to the moon and Mars once, did I ever tell you that?”

“You wanted to be an astronaut?”

Lou nodded.

“I saw you reading those magazines.”

“I used to read a lot of that stuff, especially in Nam. I needed it to escape. I hadn’t known anything could be like that place. The things I expected and the things I saw there were different, you know? I’m sorry. I don’t want to spoil it for you.”

“Vietnam?”

“No, the moon.”

Beyond Lou’s head, a spotlight had fixed on a portion of the smog cover and was becoming brighter.

“You didn’t, Uncle Lou. It wasn’t you. It was the TV.”

He stopped, his breath gone, and stared in awe at the sky. The spot of light was the moon, shining through the smog: now brown, now the yellow of old paper, now white.

“Look!” he said.

Lou sat back and looked up, smiling. The smog started in on the moon, billowing over her face, softening her edges. Jeff looked away before she vanished.

“Here, Jeff, let me help you up. I want to show you something.”

Uncle Lou not only pulled him to his feet, he lifted him over the picket fence and steered him into the garage ahead of Mab, with a firm hand on his shoulder. Jeff looked around at the stark-lit room where everything—stacks of newspaper, tools, jars of nails, even the windshield of the broken-down car—was covered with a layer of dust. Lou moved him off to one side and reached into the shadows beneath the high cabinet. “Have I ever shown you this?” he asked.

When he turned around, he held an ungainly wooden tripod together with a long gray cylinder.

“A telescope!” Jeff said, and as he took a step toward it, Lou aimed the neglected barrel and blew a cloud of dust into his eye.

* * *

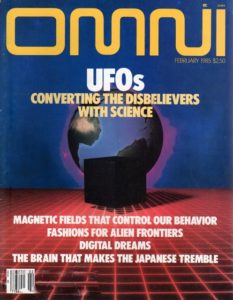

“Sea of Tranquillity” copyright 1985 by Marc Laidlaw. First appeared in Omni Magazine, February 1985.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

At one point in my early twenties, burned out on science fiction and questioning why I wrote the sort of genre pieces I wrote reflexively, I wrote a book made up of semi-autobiographical pieces, all set in and around Los Angeles, where I lived until age 10. At one point not long after that, I threw the book away, except for this chapter, which I held onto probably because it had some genre interest. As an exercise in memory, I find it unsatisfying now because I scrubbed out one of the most interesting details of my childhood. My uncle was not a red-haired white guy, as I have him in this story, but a full blooded Hawaiian. The real man was so much more interesting than the generic angry uncle character in this story; he had been a star quarterback of Honolulu High School, then a sergeant in Viet Nam, always warm and humorous. I guess I felt the real person was so much more interesting than the rest of the story that he’d detract from the lunar landing. I was probably right that I wasn’t a strong enough writer to do the real person justice, and I also might have been shy of writing about my family except in the most generic terms. So I scrubbed this piece clean of what now seems to me the most interesting thing about it. I wish now that I had been a little braver.